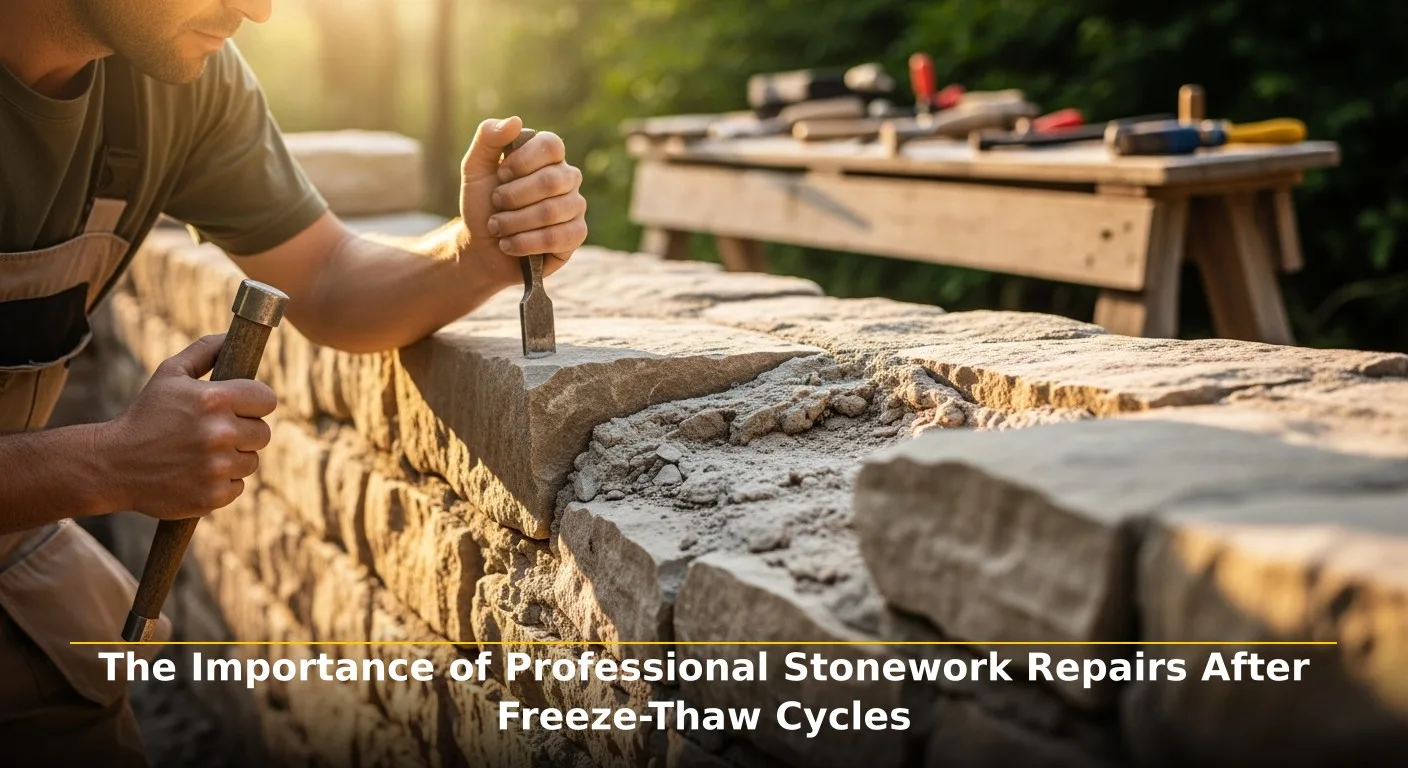

After a long Minnesota winter, the visible damage to stonework—a few cracks, some flaking surfaces—can seem like a minor cosmetic issue. However, these superficial signs are often the tip of the iceberg, indicating profound structural compromise caused by relentless freeze-thaw cycles.

For homeowners in Rochester, the Twin Cities, and across the North Star State, attempting DIY repairs or ignoring damage can transform a manageable restoration project into a catastrophic and costly failure. This guide explains why professional assessment and repair are not merely a recommendation but a critical investment in the structural integrity and value of your property.

1. The Silent Assault: How Freeze-Thaw Cycles Systematically Damage Stonework

Minnesota’s average of $90+ annual freeze-thaw cycles acts as a relentless, destructive force on masonry. Damage is not superficial; it is a systematic failure beginning at a microscopic level.

A. The Physics of Destruction: From Water to Ice

Porous stone and mortar absorb moisture from rain, melting snow, and ground humidity. When temperatures drop, this trapped water freezes. As water freezes, it expands by approximately 9%, generating immense internal pressure—over 50,000 psi—within the stone’s pores and mortar joints. This pressure far exceeds the tensile strength of most masonry materials.

B. The Progressive Failure Pattern

This pressure acts, causing a predictable pattern of damage:

- Micro-fracturing: Initial freeze events create miniscule cracks within the stone and mortar.

- Crack Propagation: With each subsequent cycle, water enters these micro-fractures, freezes, and expands, widening and extending the cracks.

- Spalling: When cracks near the surface, the pressure pushes thin layers of stone face right off the wall. This spalling is a clear sign of advanced internal damage.

- Mortar Joint Failure: Mortar, often more porous than the stone itself, deteriorates first. It crumbles, erodes, and recedes, losing its bond and ability to hold the stonework together.

- Structural Weakening: As mortar fails and stones crack, the wall or facade loses cohesive strength. What was a monolithic structure becomes a collection of loose, compromised components, leading to bulging, leaning, or even collapse.

Visible Sign | What It Often Indicates Beneath the Surface |

Spalling (Flaking Stone) | A network of internal fractures; compromised stone integrity. |

Crumbling Mortar | Loss of structural bond; potential for water infiltration behind the stone. |

Efflorescence (White Chalky Residue) | Persistent moisture movement dissolving and depositing salts within the masonry. |

Small Surface Crack | A deeper crack that acts as a gateway for more water and damage. |

2. The DIY Pitfall: Why Well-Intentioned Fixes Can Cause Catastrophe

For freeze-thaw damage, using hardware store products and a weekend project approach is fraught with risk.

A. The Incompatible Materials Trap

- Wrong Mortar: Utilizing standard concrete mix or a mortar that is too hard (high Portland cement content) is a critical error. Hard mortars trap moisture, prevent vapor transmission, and concentrate stress, causing the adjacent stone to spall around the repair. Professionals use lime-based or specially formulated mortars that match the original’s strength and flexibility.

- Film-Forming Sealants: Applying a non-breathable, acrylic-based sealer from big-box stores traps moisture within the stone. This guarantees that any remaining water will freeze and cause more severe spalling, effectively accelerating the very damage you’re trying to prevent.

B. The Symptom-Only Treatment

DIY repairs often address the visible symptom while ignoring the root cause. Filling a crack without diagnosing why it formed—includinga faulty gutter, poor drainage, or a failing chimney cap—is a temporary fix. The water will simply find a new path, causing damage elsewhere.

3. The Professional Restoration Process: A Systematic Approach to Longevity

Professional masons don’t only “fix cracks”; they perform a comprehensive restoration that addresses past damage and prevents its recurrence.

A. Step 1: Forensic Diagnosis and Assessment

Certified masonry professionals begin with a thorough investigation:

- Moisture Source Identification: Tracing the path of water intrusion, checking for issues like faulty flashing, clogged weep holes, or improper grading.

- Structural Evaluation: Assessing the entire structure for lean, bulge, or other signs of movement.

- Material Analysis: Identifying the type of stone and the original mortar composition to ensure repair compatibility.

B. Step 2: The Repair Protocol: Precision and Compatibility

- Repointing (Tuckpointing): Professionals carefully grind out deteriorated mortar to a depth of ¾ inch or more. They then repack the joint with a custom-mixed mortar matching the original in composition, porosity, and color. This restores the structural bond and allows for proper moisture vapor transmission.

- Stone Replacement and Repair: Damaged stones are carefully removed and replaced with matching stone.

- Crack Stabilization: Significant cracks are cleaned and injected with specialized, breathable masonry epoxies.

C. Step 3: Preventative Protection

Once repairs are complete, the final step is to apply a professional-grade, vapor-permeable sealant. These silane/siloxane-based products penetrate the surface to form an invisible, breathable water-repellent barrier. They repel bulk rainwater while allowing inherent moisture within the masonry to evaporate, breaking the destructive freeze-thaw cycle at its source.

4. Case in Point: Professional Intervention in Action

A homeowner in Southwest Minneapolis noticed spalling bricks and crumbling mortar on their 1930s chimney after a severe winter. A DIY attempt to patch the mortar had failed within a year, and the spalling had worsened.

A masonry contractor discovered the original lime-based mortar had been improperly repointed with a hard Portland cement mortar decades earlier. Trapped moisture led to accelerated spalling of the soft, historic brick. The chimney crown was also cracked, allowing water to pour into the structure.

This chimney was carefully repointed using a soft, lime-rich mortar mix, and severely spalled bricks were replaced with period-matched salvaged brick. Its crown was rebuilt with a reinforced, sloping concrete crown, and the entire structure was sealed with a colorless, vapor-permeable siloxane sealant. Structural integrity was restored for the long term, avoiding a costly full rebuild.

Conclusion: The True Cost of Inaction

After a Minnesota winter, damage to your stonework is a call to action. Choosing a professional repair is a strategic investment. It preserves the structural safety, historical integrity, and financial value of your home. While the initial cost of a professional may be higher than a DIY attempt, the long-term value is incomparable — decades of protection, peace of mind, and the avoidance of a total rebuild that insurance will not cover.

FAQs About The Importance of Professional Stonework Repairs After Freeze-Thaw Cycles

1. My insurance covered a recent ice dam issue. Will it cover freeze-thaw damage to my stone facade? Typically, no. Homeowners insurance covers “sudden and accidental” losses (notably a tree falling through a wall). Damage from freeze-thaw cycles is classified as a maintenance issue resulting from long-term wear and tear, which is explicitly excluded from most policies.

2. How long will professional stonework repairs last? A professionally executed repair using compatible materials should last as long as the original work—often 25 to 50 years or more. Achieving longevity is the correct mortar and the application of a breathable sealant.

3. Can I just seal the damage without repairing it first? Absolutely not. Applying sealant over existing cracks and spalled stone will trap moisture behind the sealed surface, guaranteeing that the freeze-thaw damage will continue and worsen out of sight, leading to more extensive and costly failures.

4. What time of year is best for these repairs in Minnesota? Late spring and summer are ideal. The warm, dry weather is necessary for the mortar and sealants to cure properly.